Booksellers: We Got Shakespeare's Personal Dictionary on eBay

But scholars say the handwriting in the margins may tell a different story.

Scholars say that William Shakespeare used as many as 30,000 different words in his plays and poetry. They further estimate that he knew about a quarter of all the words circulating in English during his lifetime.

This is remarkable, and it raises a question: How did he learn them? Some, we know, he invented; some he borrowed from Latin or French. But others he simply looked up, in any one of a number of reference books available to Londoners in the late 16th century.

Now, two New York City booksellers say they have found one of those books. And it's not just any guide: This is William Shakespeare’s dictionary, owned and annotated by the man himself.

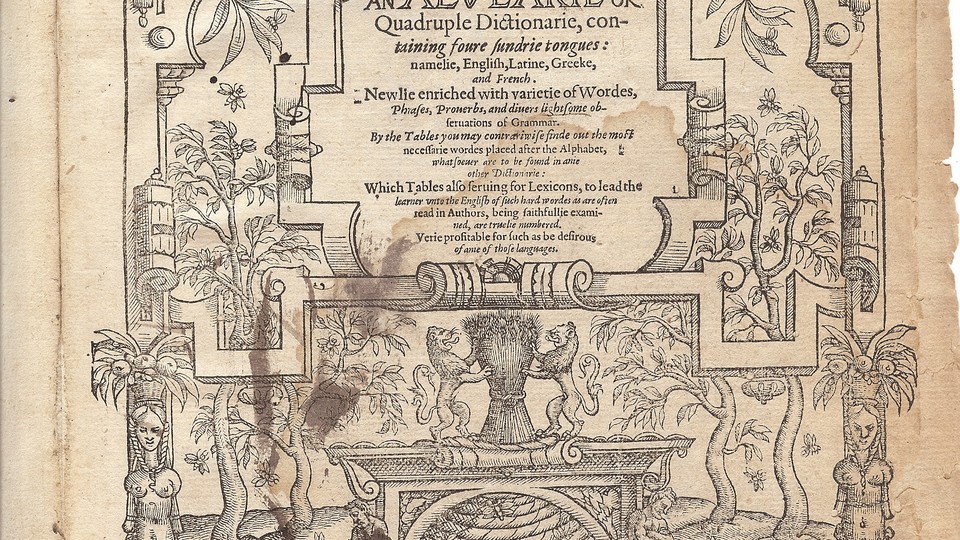

For more than half a century, many scholars have believed that Shakespeare consulted a 1580 dictionary published in London called An Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie. Assembled by Cambridge Latin instructor John Baret, the Alvearie was one of the most popular dictionaries of its time. It was "quadruple" because it covered four languages: English, Latin, Greek, and French.

T. W. Baldwin, the first critic who argued for Shakespeare’s use of Alvearie, made no claim that the Bard used a certain copy. The evidence, he said, just pointed to Shakespeare consulting some copy of the reference guide for his work.

Other scholars have agreed. In 1996, Stanford professor Patricia Parker wrote that Hamlet’s speech to the players resembled Baret’s ideas about interpretation.

Now, two antiquarians, George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, believe they’ve found the copy. It surfaced on eBay, naturally, where the book's 1580 publication date and a seller's reference to "contemporary annotations" caught Koppelman's eye. Suspecting the book was what he now believes it to be, Koppelman paid $4,300 for it in 2008, he told the New Yorker.

Once he and Wechsler had their hands on the Alvearie, they studied its annotations for evidence that Shakespeare himself had scoured and marked up the pages.

This, they say, is indeed Shakespeare’s Alvearie.

Koppelman and Wechsler announce their work in a new book of their own, Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light. It seems to be half-reproduction of the alleged dictionary and half-discussion, and it’s accompanied by a website that itself includes photographs of the Alvearie.

Already, though, senior Shakespeare scholars have publicly doubted the announcement. There isn’t yet a preponderance of evidence, they say, to prove this book was the Bard’s.

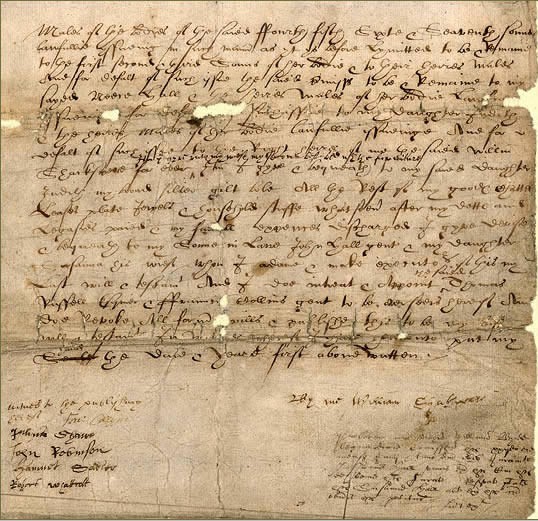

If the two booksellers are right, the finding could add a great deal of knowledge to contemporary understandings of Shakespeare. Although he has given rise to reams of scholarship and speculation, the material legacy of William Shakespeare—the objects known to have been owned or touched by him—is pretty slim. Scholars know him to have signed all of six legal documents, and he perhaps hand-wrote three pages of an unpublished play.

A whole new annotated book, and a proverbial dictionary at that, would be a major find.

But let’s step back. What makes Koppelman and Wechsler so sure this Alvearie is Shakespeare’s?

According to Henry Wessells, another antiquarian who had early access to their work, Koppelman and Wechsler see Shakespeare’s hand in two kinds of annotations. First, there are mute annotations: handwritten “underlinings, slashes, and other small marks” that don’t accompany any added words. Then, there are small spoken annotations, new handwritten words commenting on the dictionary.

The second half of the new book by Koppelman and Wechsler, writes Wessells, links these two kinds of annotations to notes and ideas in the plays. In other words, where Parker matched Hamlet’s theatrical directing and Baret’s ideas about interpretation, Koppelman and Wechsler say they've found annotations in the Alvearie that support the idea that Shakespeare borrowed ideas from it for Hamlet. They believe Shakespeare didn't just use the Alvearie as a writing reference, but considered the dictionary's guidance on language usage in how thought about the interplay between language and theater.

Wessells writes that he’s a long-time friend of one of the two antiquarians. In a blog post, he says he supports their theory, though out of the strength of the evidence, not his relationship with one of the authors. Fair enough—early modern English bookselling is a small word—especially since Wessells makes it clear that he lacks the specialized knowledge to specifically confirm the Alvearie claim.

That did not keep him from finding beauty in the attempt. He writes:

The ordinariness of the individual annotations is, to me, precisely what argues for their authenticity : they form not a rough draft of any single text, but a tool kit. The connections between Baret’s word store and the plays and poems all point to the transformation that occurs in the space between an author’s notes and composition : the play of language.

If any independent organization could verify—or nix—Koppelman and Wechsler’s claims, it’s the Folger Shakespeare Library. Located in Washington, D.C., the Folger is the largest library of printed Shakespeare material in the world. It also has a huge archive of handwritten and printed material from other contemporaries of Shakespeare.

On Monday, two senior scholars at the Folger wrote a blog post to reply preemptively to Koppelman and Wechsler.

Michael Witmore, the Folger’s director, and Heather Wolfe, the library’s curator of manuscripts, said they couldn’t yet celebrate a new part of Shakespeare’s material legacy.

“At this point,” they write, “we as individual scholars feel that it is premature to join Koppelman and Wechsler in what they have described as their ‘leap of faith.’”

The two Folger scholars hold up four different research methods that scholars will use to get at the identity of the dictionary’s annotator. (Their post, by the way, is superb, and worth reading in its own right.)

The first is paleography, or the study of old script. The handwriting in the Alvearie is italic-style, but almost all of the existing samples of Shakespeare’s handwriting are in a different form, called “secretary.” But we know from other annotated books dating back to the 16th century that other writers made notes in italic or a mix of the two styles.

So the writing of all those other margin-scribblers has to be compared against the Alvearie's writer: Can every writer who's not Shakespeare writer be ruled out?

Second, Shakespeare was sometimes the only writer of his period to use certain words. Has the annotator of the Alvearie marked these unusual words—a hint that perhaps Shakespeare was the one doing the marking—or not? (And if not, did the annotator mark other words that Shakespeare never would have used?)

Third, dictionaries during Shakespeare's life listed synonyms or related words as much as they defined. Koppelman and Wechsler say that the related words given by the Alvearie match synonyms that are close together in Shakespeare. Witmore and Wolfe question: “How likely is it that Baret’s Alvearie—as opposed to proverbial wisdom and common association—is the only possible source for Shakespearean associations?”

Finally, there are many books with marginalia from the period, though none are known to have been annotated by Shakespeare. Does the marginalia in the Alvearie look like it might be written by another author whose marginalia survives better?

Witmore and Wolfe write that, although they would love to add a new object to the known material legacy of Shakespeare, they must do it with extreme skepticism:

Scholars, however, will only support the identification of Shakespeare as annotator if they feel it would beunreasonable to doubt that identification. This is a fairly high evidentiary standard, since it requires one to treat skeptically the idea that this handwriting is Shakespeare’s and to seek out counterexamples that might prove it false.

It’s a high standard, but worthy of the legacy of the bard. Over the next months—indeed, likely over the next years—scholars will seek to understand how this new finding shapes or changes our understanding of the English language’s most famous writer—if, indeed, it does at all.

As scholars debate and discuss the question, they’ll do so in writing, a kind of additional marginalia to the Alvearie’s scribble. And they’ll be helped by the considerable resources placed online by Koppelman and Wechsler, like high-quality scans of the whole book. The sites themselves, and the openness of the scans, seem to make our incredible new information technology worthy of an earlier era’s: Shakespeare had his own new IT, a thriving print culture that was just coming into existence.